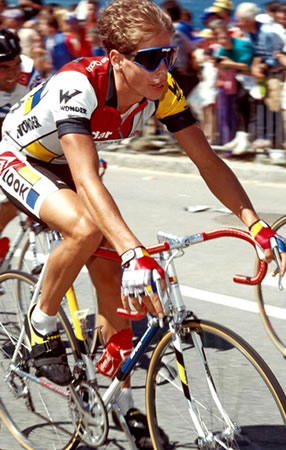

schmalz It’s a pleasure to talk to you. If US cycling had a Mt. Rushmore I think you’d make it to the front.

Hampsten (Laughs)

schmalz I think you’d make one of the four faces on the Mt. Rushmore of American cycling.

Hampsten Thank you. That’s a great thing.

schmalz You grew up in North Dakota, you probably got 45 minutes of summer, I assume.

Hampsten That’s about it, and it was hot and windy.

schmalz So how did you get into cycling growing up in North Dakota?

Hampsten Because I grew up in North Dakota. Both my parents were teachers, so they’d get the summer off. So we’d go camping all around the mountains in western United States and Canada for two, even three months of the year. I traveled a lot when I was a little kid, and then as a bigger kid. So I definitely had a little wanderlust to get out of the flat plains. When I was 15, my family spent the summer in England, and there I rode and raced with the Cambridge Town and County Cycling Club. Weekly time trials, criteriums, but mostly I just hung out with a lot of cyclists, really nice bike club, read about the Tour de France, which I had no idea existed. Just had a really good time riding with other people.

schmalz When you were younger was there any sort of indication that you had the talent that you had? Were you dropping people right away?

Hampsten No, when I was 13 I got my first ten speed with my lawn mowing money, and there were half a dozen good cyclists in Grand Forks, the town I grew up in. All older people, coached, and I was coached, and they would teach me how to draft, and we’d ride every evening, these 15 mile rides, and weekends we’d do longer rides. So they’d teach me how to draft, so they could get me home and not worry about me. But I didn’t race very much until I was 15 in England, I did a lot of time trials and criteriums, but not winning. Actually, I won a training race, the first race I won, I was 15, but racing against the seniors, and it was a hilly circuit. It’s not a very hilly area in Cambridge, but it was a hot day, we had two days above 80 degrees that summer in England. I won and my brother was second, so I thought it was just pretty strong British racers wilting in the heat. It really wasn’t until I was 16 and started racing at the national level that I got an idea how good I was.

schmalz That’s probably when you first came across Greg Lemond, I would assume.

Hampsten Not quite. Certainly reading about him, but he was still a couple stratospheres above. Even the junior races would still have fields of 80-100 in the Midwest, pretty competitive racing. I don’t think I had a Lemond sighting until the next year.

schmalz How long did you have to travel to get to races in North Dakota?

Hampsten I had to move (laughs), I had to move to Wisconsin. There were some races, I remember as an intermediate driving five or six hours, sleeping in the car, doing the state time trial championships up in Bismarck. It was hell, and I didn’t have a car, so there was one race when I was 14 where I rode my bike 80 miles to Fargo, and then drove in the back of a pickup through the night, and we raced in, I think, Rapid City the next day, and drove back, sleeping with friends. But it included an 80 mile commute each way to get to the race.

schmalz Kids these days don’t realize how good they have it, do they?

Hampsten On the other hand, it was the perfect…I didn’t learn a whole lot about tactics, if you will…it was the perfect training to be a pro later on. If I wasn’t eager enough to ride my bike that far to get to a handful of races I could in a year I don’t think I could’ve the mental skills or lack of good sense later on as a pro to keep at it.

schmalz An 80 mile North Dakota ride you could come into all kinds of weather on the way there.

Hampsten Or the steady 20 mph wind out of the south.

schmalz That’ll toughen you up.

Hampsten There was a lot of really nasty weather. When I was a kid I’d train on the road if it was above 20 degrees. If it was below that I’d ride my bike to school every day growing up. The little cycling abilities that I developed as a kid helped me when the going got really tough as a pro.

schmalz And you did pretty well one day in the cold…

Hampsten It was actually a couple of days. Photographers were there on the Gavia, so that was my fifteen minutes.

schmalz When did you turn pro?

Hampsten I did four years as an amateur. I turned pro in May of ’85, which would’ve been my fifth year of being an amateur.

schmalz And how old were you?

Hampsten I was 23.

schmalz What was the first pro team you raced with?

Hampsten 7Eleven recruited me on a one month contract to do the Tour of Italy.

schmalz And that’s where you won a stage.

Hampsten Yeah.

schmalz So, first stage race, and you came away with a stage win.

Hampsten Yeah, which also answers your question "When did I think I was going to be really good?"

schmalz That was it, eh?

Hampsten Yeah, winning a stage as a pro.

schmalz What was that stage like, was it a mountain stage?

Hampsten Yeah, it was a very short mountain stage, I think it was a 57k stage where we raced 35k’s up a valley and we went up I think a 17k climb. Not terribly steep, if you recall the profiles of the Tour of Italy when Moser was racing, it was very very tame compared to this year. There weren’t many mountain stages, and I was getting stronger as the race went along. It was the 20th stage, or 19th, it was getting to be the 3rd week of the race. The team just led me out, I did a really nice warmup in the morning, I was pretty disappointed with the climb, because it wasn’t very steep, and it was pretty dull towards the end. My coach, Mike Neel, just picked a corner for me to attack about 1k into the climb. It was fairly steep, 10% or so, big wide road. He told me the other racers knew I was doing well because I was in the first group on all the climbs, and I needed a bit more surprise on everyone. I wasn’t high on GC, I wasn’t a threat to the top riders.

So the team led me out to that one point, and I was wearing a one piece, and a lot of the other pros were teasing me, being a dumb American, amateur, for wearing a one piece, ’cause of course, that’s never done on a road stage. And we kicked their ass. It was pretty fun.

schmalz That piqued the curiosity of the La Vie Claire team for you, then.

Hampsten Yeah, it did. Greg Lemond was third on that Giro so he was on the team, he was very excited just to have some English speaking company with his buddies on the 7Eleven team. He’d already told his team, "Watch this Andy, he’s a really good rider", and he’d go tell me, "Hey, I just told them you’re a really good climber, go do something! I’m trying to get you on the team, you need to get some results!"

schmalz "Don’t blow it, Andy." No pressure.

Hampsten I was pretty stoked to win a stage. That convinced them I’d be a good addition to the team.

schmalz You had good early stage racing, not only did you finish your first Giro, you won a stage, and then the next year you go to the Tour, the 1986 Tour, which was one of the most dramatic Tours you can find.

Hampsten I think so! I’m a spectator, now, I think that was the best race ever. As a participant that year, it was horrible, teammates fighting over who got to win the race, which was interesting, but it wasn’t any fun being on the team.

schmalz Going into the race, was Greg convinced that because of all the work he did for Hinault in ’85 it was his year to win the race?

Hampsten Yeah, Hinault had been telling all of us, that we’re just going to help Greg win the Tour. In July, Andy, your job is to climb really well and help Greg win the Tour. Plan A for everyone. It wasn’t until the Tour started that Hinault changed the plan, and was racing for the win also.

schmalz And lo and behold, he had a five minute lead by stage 12. Just out of nowhere, I guess. I think he did try to explain that later by saying he was trying to soften up the race for Greg.

Hampsten Well, he did. The first day in the mountains, I think the Marie Blanc, we had something NASTY in the Pyrenees, and at the top there were about fifteen racers, it was Greg, Hinault, myself, and another guy, but he was pretty tattered. And Hinault was doing tempo, and I remember it was 100 some k to go, there was nothing up the road as I recall, he’s just doing tempo to keep it hard. And I thought that was really weird, and I asked Greg about it, and he thought it was really weird. I went up and asked Mr. Hinault if he’d rather I did the work instead of him, and he was pretty snarly and gruff about it. I started doing tempo, but I didn’t really know why. But then Hinault attacked‚ I can’t remember if he went with an attack or he attacked‚ but he was gone with a long ways to go. But he did destroy the field. His explanation after the stage was, "It was all broken up, first day in the mountains, you can’t just sit around, we’re La Vie Claire. We have to be aggressive, we have to take action."

His excuse was "I just attacked to see what was going on. I knew that behind Zimmerman and Breukink and all the favorites would have to chase me down." Which is absolutely true.

schmalz And if he were to accidentally win the race, well, so be it I guess.

Hampsten Yeah, attacking the second day, getting another five minutes up the road, making the same competition chase him down, you can argue that was an honorable thing to do. You can say it was an error getting five minutes, you can argue the chase should’ve been successful chasing that breakaway, Greg should’ve taken off in the final hour. So instead of sitting and enjoying his five minute lead, he did repeat the same move farily suicidally the next day, and lost almost all of his five minutes.

schmalz That had to be some awfully awkward breakfast conversations.

Hampsten Dan, it was THE worst breakfast situation. Actually, the evening after the second day in the mountains, where Greg wins the stage, Hinault loses, ironically enough, almost five minutes, and Greg had the jersey. It was horribly awkward, and in the meantime, Bernard Tapie, the owner of the team, was helicoptering in, and he was going to straighten out the Hinault situation. ‘Cause the French guys didn’t like it, Steve Bauer and I hated it, the Swiss guys were out of their minds with all the stress. And Tapie shows up, has a private talk with Greg, a private talk with Hinault, kind of looking for a sign that all’s cool. So Greg comes to the table, Steve and I are like, "W-w-well?"

"He didn’t do shit. There is no resolution, nothing’s changed, Hinault’s just going to do whatever he wants. He’s Hinault."

So Tapie walks into the room, everyone’s sitting down, this table of riders, table of support people, he walks in, bold Izod colors on his shirt, turned up, he’s just larger than life, strutting around the room, and we just understood, he’s all hot air. It’s just this horrible silence in this entire room, and Tapie’s just completely changing the subject that the entire Tour de France wants to know, but no one wants to know more than our team. When is this bickering going to end.

And Greg Lemond cannot sit in a room for more than two and half minutes and not have fun. It doesn’t matter how stressed he is, he’s gotta have fun. So he breaks the silence with…well, that day, I had taken over the white jersey. Jean-Francois Bernard had had it earlier, and before the Tour started, Bernard Tapie very publicly to the press, "my adopted son, Jean-Francois Bernard, WHEN he wins the white jersey, I’m going to give him the keys to my Porsche 911." So the press is always pestering him about it, ’cause he had it up to this point.

So Greg says, "Hey Tapie! Now that Hampsten has the white jersey, you gonna give him the Porsche?" Only three guys laughed, the whole room…

schmalz And the Porsche is in your garage to this day, isn’t it?

Hampsten No, the Porsche never came my way.

schmalz What was it like being Hinault’s teammate? Were you afraid to ask him to pass the salt when you were at training camp? Was he intimidating?

Hampsten No, he was the nicest teammate you could possibly have. His last year, he was grumpy. You see this with older people (like me) and older riders. They don’t like training in the rain, every time it snowed, one snowflake, the entire team would go to him, "Hey, this is like Liege Bastogne Liege, 1978 when you…"

In his last year, he was looking forward to retiring. He obviously liked racing, it was fun, but he wasn’t patient with the bullshit. He didn’t like to be teased by other riders, he had a huuuuge reputation, he really just wanted to get home and farm and get all this racing behind him. But if he was going to race he was going to be serious about it. But he was also extremely generous with his knowledge with anyone on the team, especially younger guys who asked or showed respect.

I didn’t speak much French, I took it in school, but that just didn’t help, I learned by hanging out with French guys. I remember our first race in early February in Spain, he was the leader on our team, a crosswind section came up, he was at the back and I had to bring him forward. So I found him, got him, made sure he was on my wheel, and I wasn’t really fit, and the Spaniards were raging, because the Vuelta used to be in April. February down there, they were just all guns blazing.

So, no big deal, I’ll get him to the front. But riders were in the gutter, and I’m just staying a foot or so away from the riders in the gutter, as amateurs, that’s just what we did. And Hinault after about 40 seconds of that nonsense, puts his hand on my hip, gently pushes me out into the wind, into the middle of the road, away from all of the riders, and just said, "Take me as far as you can", and I was completely in the wind, not that I was getting much shelter before, got him all the way there, and he went and did his business. I talked to him after the race, he came to me and said, "Thank you very much for helping me, the only way I want that kind of help, no offense, but I don’t want to mess around with those other dogs. If you only take me ten meters up the road, I don’t care. I don’t want to crash, I don’t want to deal with that nonsense."

And I just thanked him and thanked him, "I’m here to learn, you’re the best. Just tell me how to do it." Other times, when he had flats, this was the same race, he had a flat over the top, and there was only twenty or thirty racers at the front of the race, and the descent was really gnarly, just a bad bumpy road, and I waved him forward, because I didn’t dare go fast enough to go faster than the front group, and I knew we weren’t getting time. He never passed me, and I had to slow down quite a bit, and we got to the bottom, and he said, "Ok, now go". We could see the group 30 or 40 seconds ahead.

And again, he came to me afterwards and said, "You know what, we’re racing in Spain, it’s February, I don’t want to crash. If you can’t go fast enough I sure don’t want to follow you any faster." He was very very generous teaching people how to work for him, and then when teammates had the race lead, and the most obvious example for me was the Tour of Switzerland, I won the prologue, and the next day we did four laps up a fairly hard circuit, but it was going to be a sprint finish, but I was too proud to wear a rain jacket, and I’m bonking towards the end of it. He came and found me in the pack with 20k to go, and said, "Well, how do you feel?"

And my other teammates were just telling me, "Hey, Andy, if you have a problem let us know, but we’re going to try to win the stage." The team was just to protect me, but he went and found me, saw that I was shivering all day, and I just said, "I’m not good, I’m in trouble."

He said, "No problem." When we were on little hills, he would take me out, in crosswinds, he would take me out to the open road, sit up really tall, give me a big draft, and he’d let us both just slide back on the uphills. We were just doing rollers. We’d slide back on the uphills and he’d bomb the downhills and take me to the front. He showed by example, he repaid his teammates by helping domestiques win major races.

schmalz Do you think that Bernard and Greg have gotten past what happened in ’86?

Hampsten I don’t know. All I know is what I’ve read. I don’t know if they’ve gone out for beers and gotten over it. I understand Hinault’s point. What he said after the races was "I said I’d help him win the Tour de France, but you can’t just GIVE the Tour de France to someone." And I certainly understand Greg being upset that his teammate told him one year he’d help him win and then raced against him.

schmalz It seems like Bernard did the exact opposite with Greg than what he did with you in the Tour de Switzerland.

Hampsten Sure. But he didn’t care about the Tour de Switzerland. He raced against his teammate and tried to win for himself at the Tour de France, which was, I think, something he’d never done before. Helping me win the Tour de Switzerland is just helping some domestique on the team win a huge race, which is actually a feather in the cap of a top racer, to say…he was already second or third in the prologue, he was right up there…for him, it was more prestigious a lowly teammate win the race than to win it himself.

schmalz Then in ’87 you moved to 7Eleven. How do you explain Alexi Grewal to people?

Hampsten Don’t know. He was a super, super crazy good racer when he was young, but he went to Panasonic, perhaps the top amateur pick in ’85, but living as a pro is really really hard off the bike, and Panasonic was the toughest, nastiest efficient race winning machine he could’ve chosen.

schmalz It just kinda got to him and tore him up?

Hampsten Yeah, I imagine there was quite a bit of that.

schmalz 7Eleven and Motorola, in the early days, it was a pioneering thing still, to have an American team going over, so do you think your role on the team was to give the team more respect overseas?

Hampsten Yeah, definitely. I had a lot of offers from good teams but I, especially after that La Vie Claire experience, and Paul Koechli, who was the coach that year, was the best coach possible that I could’ve worked with, that the team could’ve had. Certainly after all the politics on a French team in ’86, I knew I couldn’t race with that. It was a risk going with 7Eleven, ’cause for stage racing I was the most experienced rider, there weren’t proven domestiques that were great at mountainous racing to back me up. But I believed in the team and I believed in Mike Neel’s coaching, also I thought Jim Ochowicz would do a really good job managing it, I was more excited about racing and living in Europe, racing for an American team, rather than racing for…I really liked La Vie Claire because of Paul Cokely, philosophically we really really agreed on a lot of things, so I could’ve stayed on that team. But after ’86 I could tell he wasn’t in charge of running the team the way he should be, and I didn’t want to be Greg Lemond to Jean-Francois Bernard being Bernard Hinault. I had to get off the team.

schmalz And the next year, the ’88 Giro, things really came together for you.

Hampsten Yeah, in ’87 the team was really successful, ’cause the team won the Tour of Switzerland. In ’88, since our goal was to win the Tour de France, win big stage races, it was great winning the Giro. The Tour, it was hit and miss, some years we’d win three stages, other years, we wouldn’t do very well, but they’d be big every year at the Tour, try to help me win it, which never happened, but we always gave it a good shot.

You mention, were we pioneers, I think we were. Certainly Lemond, you can look at the nice little steps in the 70’s and 80’s, with guys going to Europe ahead of Lemond, and then Lemond just busting everything down. He was a phenom. Certainly I feel now and I felt then, the whole idea was "Let’s be an American team, let’s not just copy Europeans. Let’s do what we’re really good at, and bring new things into the sport."

It was really really fun, it was also interesting at the moment thinking we’re encouraging other people to follow in our footsteps, which right now is pretty exciting. It’s really neat to see how many americans on all sorts of different teams are doing really well, and there are American teams racing well in Europe.

schmalz I think you and Greg can take a lot of the credit for what happened to American teams. I think you gave a certain credibility in the European peloton for American racers, that you could get American racers and they wouldn’t just be a novelty to make an American-skewed sponsor happy. You could actually win with Americans.

Hampsten I think Greg Lemond proved for recruiters that it’s a happy hunting ground in America, phenomenal talents available. You’re not going to find may Greg Lemonds, but I think the 7Eleven team, and I’ll take myself out of the picture as all but a tiny part of it, the entire team can jump in, Jim Ochowicz just did a phenomenal job bringing the best American over to Europe with Mike Neel being the one who knew how the game works in Europe, and making it happen. I think Greg Lemond and the entire 7Eleven team are the two pioneering points, if you will.

schmalz Now we have to talk about your win in the ’88 Giro, especially the Gavia pass. How many times have you been asked to this story?

Hampsten Quite a few! I think I’m pretty consistent with it.

schmalz It was a day when they were going to go around it, they were thinking of shortening the stage?

Hampsten They had a meeting, they being the race director with all the team directors, because it was snowing down in the valley where we were, and certainly looking at the weather report it was really bad. The meeting was communication between the highway department with their road crew and the race officials, and remember, this was in the old days, and if there was a road you raced on it. Later on there was discussion about, "Oh maybe we should’ve done something else, cancelled it", but up until next year going up the Gavia, as I understand it, politics played a very small part in bike racing. If a bridge was blown up by separtists, you found another route. Otherwise, bike racers raced, period.

If it’s a one day race and it’s snowing at Het Volk, and it’s crazy icy, then it’s too dangerous. But as long as there was a road, bike racers used to race on them.

schmalz It would require some sort of political action or explosion to get you not to race?

Hampsten The next year it was cancelled even though there was no real snow to speak of, but that was a political favor between Moser and Laurent Fignon.

schmalz How was it a political favor?

Hampsten Well, if you remember in ’84, and this is all hearsay, but I’m pretty good with my sources, in ’84 Moser and a helicopter pilot collaborated to help him and push, the helicopter pilot stayed behind Moser turning his turbines, being behind him, so the wind pushed him forward, and he won the Giro by cheating in the time trial. Against Fignon. So Fignon was leading in ’89, and Moser was one of the race directors, and essentially cancelled the stage because it was going to be cold, it snowed overnight, but it was sunny and it melted…there was some flimsy excuse that the road was out. They were talking about an avalanche in another part of the valley, that the road wasn’t good enough for the race, for the finishing equipment and the trucks to make it over. Total bullshit.

It was a bit of a… "Sorry about the helicopter, here you go."

schmalz Good to know he was able to pay him back, though, awfully generous of him.

Hampsten What better place?

schmalz Exactly. So it was a snowy morning the day you set off on stage 17, huh?

Hampsten It was 2 degrees Celsius and sleeting. They shortened the stage because of the meeting, all they did was take out 20k’s of gradual downhill at the beginning. We rode some flat, we rode a category 2 pass, and then there was a few k’s of descent, and then there was a false flat of 20k more to a town called Ponte di Legno and then there was a 22k climb over the Gavia and then a 22k descent into Bormio. The storm was coming from the direction we were descending, so we knew the descent would be worse weather than the climb.

We started the race and it was bucketing rain. We were as wet and cold as we could possibly be in ten minutes. We’re wearing all the clothes we can, there’s some grumbling about, "This isn’t right, this isn’t fair, we should form a union and strike", all this stuff. And a break went away with about 12 guys, no one really dangerous. Johan Vande Velde was in it, he was doing well, but he wasn’t one of the main guys we were worried about.

schmalz Were the guys annoyed that they broke away?

Hampsten No. No. People were out of their minds with fear. I was shivering and shaking on the false flat going up, wondering how I was going to make it over this climb, and we had great clothes. Our team went out and bought Gore Tex wool hats and gloves, we had rain jackets, we had really good lanolin, vaseline all over our bodies, not just our legs. Mike Neel had the soigneurs put waterproof lanolin all over our arms, back, and stomach. We were ready for it, but I was still frozen, literally and figuratively.

I started looking around, looking at the leaders, looking at the guys I was battling it out with, and two days before I had won an uphill stage. I was on FIRE. So, I hadn’t won a race yet that year, maybe I did, but I knew my form was coming, I didn’t feel I was anywhere near my peak. And I’d been focusing on this stage for the whole race, so I knew it would be the hardest stage. Going into it, about 10k from the climb, I just relaxed. I thought, "I’m going to go for it, if I make it, great. If I don’t, the weather is so much worse than any other day, but it’s still the simple formula: it’s a mountain day, Andy has to go as hard as he can, kind of how the team meetings went, but no one’s going to complain if I can’t do it. I’m going to complain if I don’t try."

So I ended up relaxing, taking off all of my heavy extra clothes except I kept my neoprene diving gloves on. I had a super thin polypro undershirt under my jersey. But nothing on my legs or feet, and I knew that the team car would be behind me with warm clothes for the descent. Jim Ochowicz would have a musette bag of only clothing for everyone 1k from the top, because the team car can’t service everyone on a big climb like that.

So the team, plan A, lead me to the base of the climb with about 14k from the top, my team doctor who lived in the area explained to me very well that the road would go from a nice modern two lane down to a one lane dirt road, that was 14%. And sure enough, I just had my team get to the front, all the other competitors were on my wheel, we weren’t flying, we were just doing nice hard tempo. Right at the front, which wasn’t tactically very clever, everyone was sooo freaked out about the weather, it was still snowing and just above freezing, that I attacked as soon as we hit the dirt. Hard. Not sprinting like it’s a KOM and a kilometer to go, but full on 95% effort attack, and I got away from everyone. The switchbacks were really tight after that.

I’ve been back with my bike tours after that, so I know the roads really well, this isn’t just from memory. On the switchbacks, they were 180 degrees, so I could look back and down to where I was 20 seconds ago. And I could see all my competitors spaced out, some together, some trying to ride with their teammates, but it was game on with 14k’s to go. My tactic was to go less than 100% to the top, and save not much, but save some energy for the downhill. ‘Cause I knew mentally if I wasn’t really sharp and aware I wasn’t going to make it on the downhill. And I wasn’t dwelling on how icy it would be, how cold it would be, it was just telling myself this climb’s different, don’t go 100%, save 3% for the downhill, and don’t think too much about it.

So I went at a hard steady tempo, and I was catching a lot of riders, ’cause there was a break. Some of the guys were sprinters, some were pretty good, but the only one I could gauge myself off of was Vande Velde, and I was closing on him, but I never caught him. Towards the top I put on a neck gaiter, a polypropolene sock that I knew I could pull over my nose and ears, cover my neck down to my jacket. I put on a wool hat about 3k’s to the top, and then I got my musette bag and took my plastic jacket out, and of course it was stiff. I was smart enough to keep my neoprene diving gloves on so my fingers would work, but it was really sticky on the outside, so I couldn’t slide into my jacket very well. But instead of just putting a foot down near the top and putting it on in ten seconds, I was a pro, I was too cool to do that, so I lost minutes swerving all over the road. And now the road, there’s blowing snow all over the road, it’s not icy, but there’s 2 inches of slush at the top. When I slowed down Breukink, who I was keeping at 45 seconds on the way up, he caught up with me, Van der Velde was a minute and a half, two minutes ahead of me. But I knew I had minutes on the guys I was fighting with on GC, I knew I’d gained time, other than Breukink.

And then I thought, well, this is great, if we finish where we are right now, this is a real gain. Breukink is super dangerous, but maybe I can follow him on this descent, I knew it would be slippery, maybe two would be better than one. But he was really slow and unsure on the snow, so I took the lead on the snow. It wasn’t a whiteout, you could see half a block, everything was white, there was no lead car, no lead motorcycle, there’s no one on the mountain for 12k until we got to Santa Catalina, and the road went from dirt to pavement. The snow changed to rain, and then a 13k of a pretty straight, it was always curving, but no switchbacks, just a fast 60-70k drop into Bormio.

Then at 7k to go Breukink passed me and I couldn’t even react to get on his wheel. I think I was going pretty fast, at the moment I didn’t really know. Since then I’ve been back and seen TV footage of that part, I’m pedaling really fast and tucking, it was all about the same. I couldn’t for the life of me close that 7 second gap, so I was second on the stage. But it was almost 5 minutes until the third place in the stage finished. And Chiocciolli who was the race leader, he was top ten in the stage, but he was 7 or 8 minutes down.

schmalz Most people don’t realize that you didn’t win the stage, but it did win the race for you.

Hampsten It did win the race. It was still close with Breukink, Zimmerman fought back really well with a really bold attack in the mountains, but it got it down to a two horse race.

schmalz Did you find that after you took over the pink jersey, was there any conspiring against you between Italians?

Hampsten No, I love reading the Italian cycling press, and the English press pick up on it. "Oh, we’re Italians! We’re going to work against foreigners in Italy!" It NEVER happened. It’s two guys getting together…the Italians are a lot more concerned about beating Italians than beating foreigners.

schmalz That’s interesting, that’s mostly a myth, then.

Hampsten Yeah, I guess in ’87, the year before I won, Roche won the Giro, which was unpopular, some fans were mean to him. He took over the lead from one of his own teammates, who kinda blew up. But I never experienced anything negative from fans, as far as riders, it’s very very political as you can imagine, racing a bike in Italy. So there’s people coming asking for favors, telling sweet little lies about what they’ll do for you, but it’s pretty standard operating procedure. I think there might be friends that get together, if two guys happen to be really good friends they might try to pull a fast one over someone else, but there’s really not a nationalistic tendency for Italians to ride against foreigners.

schmalz So once a pro gets paid by his team he stays paid and he stays loyal.

Hampsten Yeah, yeah. And the exception to that is if you get in a breakaway that maybe can help the guy in second place move into the lead, work a deal where you get to win the stage, ’cause he’s taking over the lead. That’s with any bike race there is, any stage race. But no, I never felt that, I was terrified of it really, but Mike Neel was really good about knowing what was going on between teams. It was pretty standard dog eat dog bike racing.

schmalz Cycling has its cloak and dagger side to it, not only what happens on the road, but different eras, different doping products and things like that. When you got into racing, I think that if anyone was going to take anything to win a race they were more apt to take amphetamins or cortisone or things like that. Your career kinda goes from that early stuff, then near the end of your career it was the beginning of when EPO started in the peloton. Could you tell when people started using EPO?

Hampsten Yeah.

schmalz ‘Cause I don’t know that the amphetamines were such, they didn’t have as much of an effect as EPO, the EPO seemed to really work well.

Hampsten Yeah, and things like a hot day, and this is just my understanding, because of course I was interested in figuring out what I thought other people were doing, but in the heat, certainly in the mountains, both cortisone and amphetamines can backfire on you. Maybe you’ll have a really good day, but most likely in a stage race you’ll blow up soon afterwards. It was really fun being a skinny climber who really didn’t understand the culture that well, to get annihilated all spring long by all sorts of guys I thought I was better than, then we’d come to May, June, the weather finally warms up and we hit some mountains, and these guys literally just disappear for the rest of the season.

schmalz The heat would just end their season.

Hampsten Yeah, and that’s basically the medical opinion I got. It’s all hearsay, ’cause no bike racer goes around bragging about the drugs they took, and certainly how they backfired. There’d just be an entire list of people who’d disappear who were good climbers, maybe they did really well in spring hilly classics, and I’d start to worry, oh my God, if they do this to me in the mountains I’m going to be in trouble. And then I’d never see them all summer long.

schmalz And in the early 90’s when EPO showed up, could you just tell, did the speed just increase by so much?

Hampsten It was individuals, individuals and their buddies, and then entire teams openly laughing at people who had much better results than they did in either time trials or climbing. Everyone knows everyone else’s relative abilities. Of course, that changes, people get better and get worse, but it was an open secret from the early 90’s on.

schmalz Was that pretty disheartening for you?

Hampsten Yes.

schmalz Suddenly people who didn’t have the same sort of abilities you had were just shooting up and taking off.

Hampsten It was PHENOMENAL. I only have myself to use as a basis, this isn’t scientific other than I had the same doctor who was my trainer, Max Testa, my entire career, and he’d test me every couple of months, so physiologically we could look at what I’d do. I was a diesel, he would call me, wouldn’t change year to year, I’d change during the year, depending on how much training I’d done. So I was pretty constant. My training always did get better, I started doing more intervals in the early 90’s, working closer with him and training instead of…in the 80’s a lot of racers would just race and do recovery rides for training, and it turned into a little less racing and a lot more specific intensity work during the training period. So I was training myself better and better as my career went along.

Certainly since I’ve stopped racing at 34, so physiologically I was slowing down on some parameters, but nothing drastic. Looking at myself, if I can stay objective about it, and certainly other guys who I knew weren’t doing anything, it went, during the 90’s, it went from "Wow, I’m not winning. It’s getting a lot harder to win a race that’s either a time trial or has hills or mountains," to "it’s really hard to stay with the first group of fifty guys."

schmalz Right. I think the advent of EPO made a lot of guys retire.

Hampsten It was unhealthy I think, to even try to keep up with the pack in some of these early season races. The pack would just go so frickin’ fast over climbs with guys like sprinters outclimbing stage racers who weren’t at their peak form. It went from kinda embarrassing for a climber to "Man, I’m pushing myself so hard in February and March that I’m overtrained to try to keep up in races.

schmalz That’s very sad. I think that American cycling has come full circle because we had you guys being the pioneers, but we also have had our troubles, I guess you’d call falls from grace, Tyler Hamilton and Floyd Landis, who have had positive tests. It always seemed like the Americans in the early days were the good guys, for lack of a better term, and now it seems like everyone has fallen into the same temptations as everyone else. I guess we’ve just come full circle and have had enough time in the peloton that we’ve just become like everyone else now.

Hampsten Yeah, I don’t know specific cases and I don’t know specifics on those, I can’t give a blanket agreement to what you’ve just stated. But it’s certainly true that the United States is, for better or worse, one of the major cycling countries in the world. Whether it’s because we have really good racers and really cool teams right now, that are yet again, cutting edge, on some very very important aspect in the sport. Philosophically, what are we doing here, why are we bike racers if we think we need to take drugs just to keep up with other people. So we’re blanketing all aspects of the sport.

schmalz You were teammates with Lance Armstrong at Motorola. What was a young Lance Armstrong like?

Hampsten Brash, super confident, didn’t like to listen, but when he learned a lesson on the bike, he only needed it once. Brash, cocky, confident, are all excellent qualities for a bike racer. So a lot of the older guys, "Wow, you were pretty stupid to attack in the feed zone, you shouldn’t do that," and he didn’t want to be told what to do, but once he made a mistake he learned it instantly. He had a really short learning curve. It was really cool to see how fast he came along.

schmalz Could you foresee the success he was going to have or did you just think he was another good racer coming along?

Hampsten Well, as soon as he was a pro he was a great racer. He won the World’s. He was just phenomenal. At Paris-Nice, we didn’t go over the top of Ventoux, we went over another climb, but he could climb with the top dozen guys over a category 1 climb. At that point, before he had cancer, when we were racing together at Motorola, I thought he could win any one day race in the world and probably any stage race that wasn’t a mountainous grand tour. When I was guessing I didn’t think he would have the recovery ability, since he weighed 170’s, I thought he could do any one mountain at full speed with anyone in the world, but he wouldn’t be able to do a series of them, and he wouldn’t have the recuperation qualities or the patience to win three week stage races.

schmalz Were you surprised when he won the Tour?

Hampsten Um…not completely. He dropped a lot of weight. If he was coming back to racing it was to win, he doesn’t race to not win. I didn’t predict he’d win, but once he had won I wasn’t surprised that he came back to racing, he lost that weight, and certainly, psychologically he was a completely different person… So, those two limiting factors, not having the patience and not having the physical stamina because I thought he was a little too heavy to be someone who could do multi mountains, those were completely different once he had his illness.

schmalz You spent a year on Banesto with Indurain, didn’t you?

Hampsten Yeah, I did.

schmalz Did you have a lot of contact with him?

Hampsten No, I wish I did. He and his brother were super fun nice guys.

schmalz It’s funny that you’ve been teammates with four of the super champions of the sport.

Hampsten Yeah, this is perhaps the most useless bit of cycling trivia. I think I might’ve been a teammate of, not necessarily during the Tour, but a teammate of the most Tour winners. It means NOTHING, ’cause I only did the Tour with Hinault, Lemond, and Lance as teammates, I was only on one winning Tour team. But if you add up Lance, Greg, Hinault, and Indurain, that’s a lotta Tours.

schmalz Sure, you’re kinda the Forrest Gump of cycling, I don’t know if that’s a compliment or not.

Hampsten (Laughs) Sure.

schmalz Not that you didn’t have your own success, but…

Hampsten Yeah, I had my own success, but that last little tidbit of useless information… It was interesting, ’cause I really liked being a racer, I liked hanging out with the guys, I liked the stress of a race situation, where it’s fun winning or protecting a lead, and an honor to be the one that won the races. But my best memories were when we didn’t win, where we chased down a breakaway, maybe when we were all riding really poorly but just for discipline we had to do something in the race, so we chased, once we started chasing we made sure we made people hurt that were just sitting on our wheels. I really like the challenges of being a bike racer.

schmalz So with cycling being in the state that it’s in today, what advice would you give to a young bike racer? If you had a son would you say go ahead, try it out, or would you be reluctant to encourage him to go into cycling?

Hampsten I wouldn’t be reluctant, I would tell them to have fun with it. Bike racing’s fun, but racing in the rain…pro racing’s not fun ’cause it’s really hard, really long, all this stress… But it should still be fun. And it’s not that I just want the whole world to have fun, it’s if you wanna be a good pro you better enjoy it. That’s a very un-European approach, ’cause a lot of Europeans just talk about the struggles, the sacrifice, they can’t wait to stop racing so they can smoke and drink and eat steak with bernaise sauce every night.

I think what helped me make it through a pro career was when I was really stressed, when something was really bothering me, when I had tough decisions, certainly when I saw EPO and other drugs fundamentally change my ability to perform in the sport, I went back to all the lessons, the only thing that really helped me was putting myself back in the same place I was when I was a teenager. Just sacrificing everything I possibly could to be a bike racer, but it always came down to, well, if you’re not good enough you’re not good enough, there’s nothing else you can do. But you can probably improve in certain areas, why don’t you go find people to help you with that. But it always came down to "How far can I push myself?", and to do that I needed to believe in myself.

And bike racing is really really fun, even as a pro. It is just a lot of fun. And I speculate that a lot of people lost touch of who they were and how much fun they had getting into the sport, and they probably made some choices that I suspect that they really regret right now, a lot of people lost themselves in cycling, and in little ways or big ways ruined themselves from the pressure, the drugs, no longer believing in themselves, and it’s those things you have to learn as a kid. Whether you’re riding or doing whatever you’re doing, if you don’t have that strength to look some really horrible options, people are going to float some really tempting options towards you, as a 20 year old that you’re going to have to live with for the rest of your life. Knowing your parents aren’t going to be there, it’s the same shit you have to deal with in high school, junior high, you know, "Come smoke some dope with us, you’re not cool if you don’t."

Same pressure that pro bike racers have to deal with, and I tell you, that takes the fun out of it. So if you can’t get through that with your own network of pretty together friends or family, your own inner strength, I propose that bike racing is NOT going to be a positive thing once you’re done with it. You can only do it until, if you’re really lucky, until your late 30’s or 40’s. You should be looking at another 40 or 50 years of fun, you know (chuckling) bragging about all your bike racing stories. It’s just sad for me to see a lot of people I raced with, a lot of people I know, being brought down the rest of their lives because of decisions they made in their twenties.

‘Bout time America’s only Giro winner got some love around here. Great job guys.

Another great one…

Thanks NYVC…

I’m surprised that Hampsten is still willing to talk about the Gavia and ’88.

The best parts were the bits about the psychology of some of the big names and the view of them from inside the peloton (Hinault, LeMond, Armstrong).

no rabbit jokes?

seriously, how does he win Alpe dHuez in the EPO era? How does Amrstrong? How about less puff and a bit more integrity?

Spitting in the soup is the dopers, Andy Shen does the real interviews, Dan is just too cozy, a la Liggett/Sherwen, think Dan could talk to Kimmage?

Hampster is just as bad for playing along, and not making a public stand, in my mind as he could have made a difference showing during that era that you possibly could win “less dirty/doped”…

whatever, it still stinks…

I dont buy it…

Frankie

It’s Paul Koechli (not Coakley). Close enough!

Firstly, thanks for reading.

Secondly, bite me.

Hampsten won the Alpe stage in 1992, which would’ve been on the early side of the EPO era – the Geweiss win at Fleche was 1994, and that’s where the EPO hijinks were thought to have come public.

I’m surprised that Hampsten is still willing to talk about the Gavia and ’88.

you are surprised that the man is willing to talk about the high point of his professional cycling career? shit i’m going to be talking about my win to my grandkids.

one of the best interviews yet

“I’m surprised that Hampsten is still willing to talk about the Gavia and ’88.”

why?

Awesome awesome awesome interview!!!

What a guy, what a talent.

Kudos to the interviewer. This site….geez it’s getting wholly forreals!

Great interview Dan.

Really good one Dan. Hampsten really comes across as a class act.

Andy is great guy. He has always been very anti doping and has shown integrity: his results do not show the talent.

He is like Mottet in some ways: one of the best of all time but he refusal to get on the sauce left him fighting for crumbs after the start of the early 90’s.

Until you get the guys from Team Cinzano, this is the best interview yet.

Thank you both.

Bernard Hinault interview would be great too.

Hampsten is one with the Ralpha.

No, the Ralpha strives to be at one with the Hampsten. The Ralpha does, however, get as close as physically and spiritually possible, but remember that no one can be at one with the Hampsten. For he is alone, in front of all of us.

and laughing with glee, I might add….

Well done! You guys are becoming downright respectable!

James Mason for Nevada City 1984.

Who’s fourth on US Cycling Rushmore? The top three are pretty obvious, but I just can’t think of a clear fourth. Unless maybe you go way back and include Major Taylor.

(Fully aware that this’ll be embarrassingly obvious immediately after posting.)

Ralpha jokes are the new Adler jokes = equally tedious

In my mind, there’s still two spots open….

Major Taylor & Fred Mengoni for cycling rushmore 3 & 4.

Nobody really wanted to put Teddy Roosevelt on Rushmore either. But he was present at the inception, and a key funder of the parks system.

black hole too tight long time G.I.

Johannes Drijer, Dutch Doping Deaths startedway before 94…

Lemond had “Iron” injections in 89 Giro, no pressure…

please interview EddyB, Mike Fraysee, Alexi Grewal, people that might actually tell us a thing, instead of scientist/journalist with too jaded/agenda to be credible…

Carmichael?

Wenzel?

Testa?

shoot for Ferrari the darklord himself?

“Did you order the Blood Red (Oranges)?”

“Si, damn right I did! People were dying from Boosting, someone had to make Orane Juice!”

Vuelta 2004

EPO first appeared on the market as a medical drug. The drug, when injected into the body, increased production of the oxygen-carrying red blood cells. It’s still used today to treat several medical conditions.

EPO benefits cancer patients with blood weakened by chemotherapy treatments. It’s also given to patients suffering kidney disease, and helps repair blood damaged by kidney dialysis. EPO, when provided under strict medical supervision, can be given safely.

But the trouble for EPO started in the late 1980’swhen the sports community discovered EPO heightens athletic performance significantly.

Magic Shoes

In 1989, seven athletes underwent an EPO experiment in Sweden. Swedish scientist, Dr. Bjorn Ekblom of the Stockholm Institute of Gymnastics and Sports, injected the athletes with EPO and then measured their endurance levels on a treadmill.

All subjects outperformed their previous endurance levels after injecting with EPO. Dr. Ekblom reported that, on average, EPO cut up to 30 seconds off a 20-minute running time. In world-class events, where fractions of a second sometimes separate winners from losers, the benefits of EPO for athletes are huge.

So why does EPO work so well for endurance athletes?

Muscles need oxygen to perform. Red blood cells in the blood carry this oxygen to the muscles. The more red blood cells in one’s blood, the more oxygen that can be carried to the muscles.

This continual boost of oxygen allows muscles to perform longer. Thus, for endurance athletes, more oxygen in their blood is like growing wings their feet. A typically grueling, uphill marathon suddenly feels like a cakewalk with EPO.

Of course, there’s a catch. A medical doctor can safely supply EPO to patients. However, an EPO overdose (a big problem with athletes and their “more is better†attitudes) results in thickened blood. When a person who’s overdosed on EPO rests, their slowing heart tries to pump this thickened blood through their body.

The result is heart failure, and usually death – hence, one of the major reasons for banning EPO from professional sports competition.

Many athletes found this out the hard way.

The Lore of Athletic Glory

In February 1990, 27-year old Dutch professional cyclist Johannes Draaijer’s died suddenly of a heart attack. This occurred roughly six months after he placed 20th in the month-long, 3,500-km Tour de France.

At the time, cycling authorities credited his death to ‘cardiovascular abnormalities’ – agitated by the rigors of his sport. However, Draaijer’s wife later told the German news magazine, Der Spiegel, that her husband became sick after using EPO.1

Overall, doctors credit EPO overdose to the deaths of over 20 professional cyclists from Europe to Central America during the late 1980’s to early 1990’s.

Of course, the lore of athletic glory isn’t only limited to cyclists. In his book, Drugs in Sports, Edward F. Dolan recounts a survey where 100 runners were asked if they’d take a drug that would make them Olympic champions, but kill them in a year.2

More than one half the runners surveyed replied yes.

I don’t think many would disagree that athletics have become competitive in all the wrong ways. I’m not sure when the change happened. I’m guessing sometime within the second half of the 20th century, when commercials and television started blending with sports.

Sporting participants are obsessed with victory. And I’m not just talking about sports on the professional levels. Amateur and masters athletes are just as crazy-competitive as the pros.

With athletics and its ‘victory at any cost’ mindset, it’s easy to see how getting any edge (even if it means using an illegal PED) is tempting. Meanwhile, PED-free athletes watch in frustration as their competitors illegally achieve record performances in competition.

Angel of (Sporting) Death

well damn it all no wonder i can’t win a master’s category race. they’re all on something–viagra, epo, activia, metamucil…

(umm, can we get back to hampsten comments?)

When Hampsten won the Alpe, he won it from a break with some other non-climbers, so it wasn’t like he hit the bottom and rode away from the field. He simply dropped a few break companions. He had been 10+mins down on GC so he was allowed to go. I don’t think it’s suspicious.

After all the complaining about descending at B-Kill, imagine coming down the Gavia on a dirt road with snow and rain.

Nice interview. Hampsten was always one of my favorite riders.

Shaw

Thank you Angel for the recap.

Shaw was totally right: Hampsten rode very steady and did not have a super amazing time for winning Alpe d’huez.

Are you rejecting armstrong just because he’s a juiced-up borderline-sociopath? I’d be inclined to agree, but then I remember that I don’t have a huge problem w/ andrew jackson on the twenty, and it seems a little unfair.

“He was very very generous teaching people how to work for him..”

Sweet read. Its great to hear first hand from they guys who made it happen.

It’s just a bitch to take replace a 50 foot granite face when things gets revealed.

Wow, Schmalz… gloves off.

andrew jackson was a total f-ckin sandbagger.

Adelbert Ames was a no-good carpetbagger, forreals.

I’m just thinking about saving the Parks Department some man hours

The current economic crisis has turned me into a brown bagger.

that is a really nice looking jersey in the last photo. does anybody know what brand that is?

If you have to ask, you wouldn’t understand.

It’s a passion, not a product.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZ5pEm3ZEn4

watch with 2009 eyes…

I really enjoyed reading that .

Brian Wolf

Andy Hampsten was able to live — and live well — in Italy after his racing career ended because he was a champion of their greatest national race and embraced their culture. I don’t think Lance Armstrong could live in France, or would want to. Thanks for the interview.

armstrong live in a france maintenant, non?

Beyonce

screw the french. they make lousy cars. ever driven a “douche-avo?”

’cause it seems like every 3 months he’s doing an interview and talking about Gavia and ’88. He must’ve recounted the story about a thousand times…

any ball he’d ring up Andy and Dan tomorrow and offer to sit down.

He can have all the adulation the world but deep down inside he hates sites like this because it has his number. He’s a self-important jerk who revels in the admiration of asskissers and followers who buy into the kool aid he’s selling.

Beat it, Armstrong, and take your starry-eyed minions with you.

Love the bit about Hinault – never heard that before. Same for a couple of bits of the Gavia tale, even though I’ve read his account of it several times in other articles. Some really solid, common sense wisdom from a very humble guy.

Tony Settel

The use of the singular in 19:21…

I have no beef w/ Lance personally … it’s just disappointing that he had to return to a sport I love and cancer it up like a cancerous cancer-filled cancer.

Good stuff Dan. You should go out and buy a fedora and write the words “scoop” onto the ribbon banding.

Totally agree with Hampten getting ‘Rushmore’d’. Loved the insider stuff. The Andy H. take on the hinault/lemond fiasco and his Giro success never gets old.

“I said I’d help him win the Tour de France, but you can’t just GIVE the Tour de France to someone.”

I like the Hinault point of view. A champion will never give away 1st place. Its just not in the DNA. I dont think Lemond could wrap his brain around that back then.

-lee3

I think Hampsten looks like David from “Breaking away.” If he’s David, then who is Mooch? Bob Roll?

is a rapha hapmsten maglia rosa replica.

if you want a great experience, go with Hampsten!

Strada Bianca!

Zi Martino’s!

Castegneto Carducci!

Mucci’s!

DSJ

Sweet interview! Thank you Andy for doing this. This was very interesting. Nice work Dan.

The original “Cutter”.

Nice job with the interview.

Dan, you forgot to ask Hampsten about his TT at Bear Mountain in `81.

Hampsten was beaten by 2 guys from the NY area – Steve Pyle and Karl Arnason.

1981 National TT, Bear Mountain, NY, Aug. 3-5 SENIOR MEN Tom Doughty, IN, 56:33.27 Wayne Stetina, IN, 57:06.02 Dale Stetina, IN, 57:26.54 Daniel Casebeer, IL, 57:42 Steve Pyle, CT, 57:59 Karl Arnason, NY, 58:40 Dave Paranka, CO, 58:42 Andy Hampsten, WI, 58:57

mighty read

is it me or does he think LA ‘s grand tour wins are surprising

wayne stetina still putting the hurt on guys more than half his age while racing masters… awesome!

Wheelsucker should be referred to using cock and the last part of his handle. This would truly indicate the type of venomous and obnoxious person he is.

As Andy’s Captain at Cambridge Town and County he was passed all the time by my mates saying we just passed Andy Hampsten on Mill Road Railway Bridge near Cambridge Station.

Cambridge is completely flat except for Castle Hill and the bridge.

The bridge was a real challenge encased in plastic like a 3 minute sauna where you lost half a stone like in a Tour de France stage but this only takes 3 minutes unless you were Andy.In which case it was bit slower.

I used to have my bike serviced at Geoffs Bike Shop in Devonshire Road at the bottom while I was waiting.

The bridge is a new training technique similar to Djockovic’s pod without any physical benefit except heat exhaustion dehydration and the loss of a half a stone in weight.

This is beneficial if you are a pieman.